There’s no business like show business—as the studios of Hollywood’s golden era can attest. RKO Pictures, the hallowed producer of King Kong and Citizen Kane, endured a stint as a rubber company subsidiary before going defunct. 20th Century Fox was joined with newspapers and news channels before being carved out and sold to Disney, says Jeffrey Miyamoto, Investment Analyst, Orbis Investments.

Disney itself has leaned for years on the profits of its ESPN subsidiary. Warner Brothers, having been merged with a magazine publisher, then a dial-up internet provider, then a phone company, is now part of Warner Brothers Discovery. Columbia Pictures has spent 35 years nestled within the sprawl of Sony. Universal was part of General Electric for decades before being sold to a broadband operator. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer is now “an Amazon company”. Paramount has spent its corporate life in and out of relationships with broadcaster CBS.

Recently, Paramount was sold again, after acrimonious negotiations that speak well to the onerous challenges now facing film studios. The old cash cows of broadcast and cable television are running dry, supplanted by streaming video, which has proven to be far less lucrative. It is unclear how or when the industry will reach its new equilibrium, and this uncertainty has roiled the share prices of companies across the broader sector.

In our view, any route to recovery for the studios will require an old partner—the cinema owners. Far more interesting to us than the studios are the exhibitors, and here, we are confident that our investment in Cinemark Holdings can recover and persist through this media upheaval.

That is not a universal view. Many continue to doubt the viability of theatrical exhibition, viewing it as another legacy business that will crumble before the rising tide of streaming platforms. But cinemas recently went through an uncommonly comprehensive test—the Covid pandemic, which proved that movie theatres play an indispensable role in making money from movies.

When the pandemic shut down theatres worldwide, studios used the opportunity to experiment with alternative ways of distributing films. Most cut down the theatrical exclusivity window—the period where films can only be seen in cinemas. Some eliminated theatrical exclusivity altogether; Warner Brothers put every one of its 2021 films onto its HBO Max streaming service on the same day as their theatrical debuts.

These tests produced undesirable outcomes. Filmmakers and actors revolted, displeased by lower pay as their compensation usually involves a cut of the box office. Christopher Nolan, a long-time Warner Brothers collaborator, was so repulsed by the studio’s emphasis on streaming that he left to work with Universal, which promised him a 100-day exclusive theatrical window for Oppenheimer. Movies, especially those published immediately on streaming platforms, were pirated at elevated rates. Most importantly, viewership analytics showed there is no conflict between theatrical exclusivity and popularity on streaming services. In fact, the most watched streaming movies are almost uniformly theatrical exclusives first.

The data shows that theatres make movies more popular and profitable. Forfeiting box office revenues does not produce worthwhile value in digital distribution, and it introduces a range of needless complications.

The major studios seemed to have learned from the experiment. They are restoring their theatrical film output and committing to theatrical exclusivity to bolster earnings and retain talent. During Covid, Disney made the money- and morale-losing decision to divert Pixar films to early streaming debuts. In June, it released Inside Out 2 with a 100-day exclusive theatrical window and achieved a record animation box office debut. Even Apple and Amazon came to acknowledge the benefits of a theatrical release strategy. Both companies have promised to spend $1bn per year on theatrical exclusive movies, or roughly ten films a year.

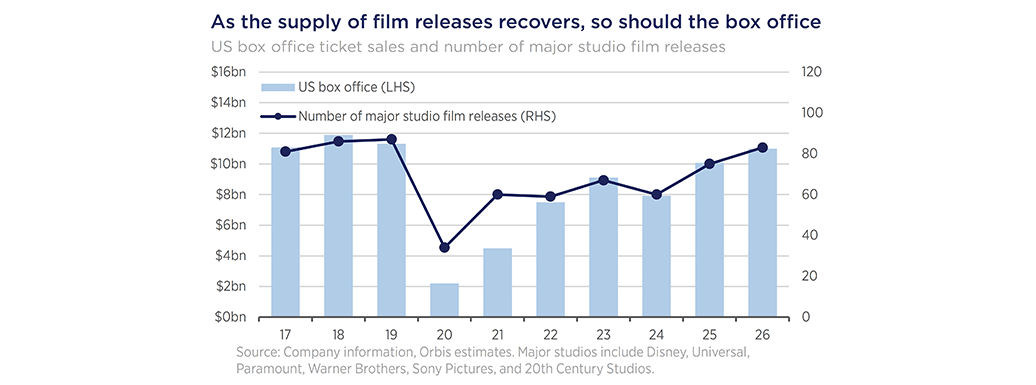

CHART 1 – Supply Film Releases

As the studios have returned to theatres, North American box office revenues have increased by double-digit percentages annually since 2020, but gaps in the schedule and the Hollywood strikes have limited the number of films reaching theatres. We expect the industry to reach pre-Covid levels of theatrical output in the next year or so. Given the tight relationship between box office revenue and the number of films sent to theatres, that bodes well for exhibitors. If the historical relationship holds, 2025 should see the North American box office comfortably exceed $10bn on an ongoing basis.

We believe no company is better poised to benefit from the anticipated box office recovery than Cinemark, the third-largest theatre chain in the United States and a leading chain throughout Latin America. Unlike many of its peers that prioritised debt-fuelled expansion, Cinemark’s management team carefully guarded its balance sheet. Its approach to expansion was cautious; the company built most of its network in suburban locations that have less burdensome property rents. It entered Covid with the lowest debt ratios and average property rents of the three national American exhibitors.

As theatrical exhibition leaves the pandemic behind, Cinemark has managed to avoid bankruptcy without resorting to dilutive share issuances. It is fully caught up on its deferred rents to theatre landlords. Moreover, Cinemark continued to invest in the upkeep and upgrade of its theatres, investing over $80m every year. Many of its peers are not in the same position, having gone bankrupt or cut reinvestment to the bone, and will still be contending with the pandemic’s aftermath years after Hollywood has reverted to normalcy.

Cinemark’s choices allowed it to achieve exceptional operating metrics even with an impaired box office. Some quarters in the last two years did have full release schedules, and those periods provide a tantalising glimpse into Cinemark’s potential. In 2023, Cinemark achieved its highest third quarter revenue ever due to its steadily growing concessions business—popcorn and drinks are the greatest profit contributors in theatrical exhibition. Cinemark invested heavily in premium amenities and better food and drink offerings through Covid, which allowed it to effectively capitalise on pent-up demand from consumers.

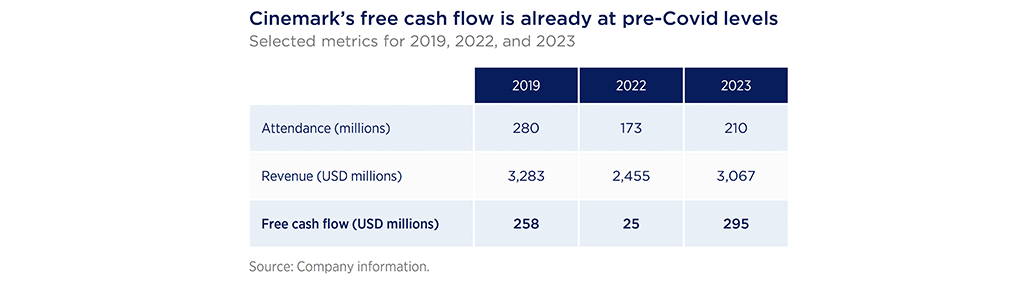

The success of this strategy is right there in the numbers. Cinemark generated $295m in free cash flow in 2023—comparable to pre-Covid levels.

CHART 2 – Cinemark free cashflow

The next few years should see the consummation of Cinemark’s business model as the industry returns to a normal film production and annual release schedule. If the box office meets our expectations, we believe Cinemark can achieve record profitability. Furthermore, Cinemark should soon restore its dividend, as the recovery brings debt ratios down to the company’s targeted window. Lastly, much of that debt will soon be gone. Cinemark has paid down $250m of its Covid-era borrowing at this point, leaving one $460m convertible bond as the final remnant of emergency pandemic debt. If Cinemark returns to its pre-Covid capital structure, we believe the shares are worth substantially more than their current price.

Theatrical exhibition is poorly understood and easy to dismiss. The best known businesses in the space are beset with challenges that will endure long after the box office rebounds. Cinemark has managed its debt and investments more prudently. The broader sector is disdained as an outdated absurdity in the age of streaming video. But cinemas remain the best way to make money from movies. Movie theatres have survived over a century of disruptions including radio, television, broadcast, VHS, home rentals, cable, DVD, and internet piracy. We believe the pandemic and streaming will join this litany of challenges overcome by theatrical exhibitors, and we believe Cinemark will lead the charge in this recovery story.

By Jeffrey Miyamoto, Investment Analyst, Orbis Investments